Turtles All The Way Down: if characters are real

Thoughts on Turtles All The Way Down by John Green - MODERATE SPOILERS

It’s my 30th birthday in a few days! I decided to share with you my thoughts on one of my favorite books to celebrate. It’s a bit of a longer essay than usual—if the email is clipped you can access the complete post by clicking the link.

Ahead you’ll find moderate spoilers for “Turtles All The Way Down” by John Green: I focus on the personal struggles of the protagonist, but I nearly completely ignore other plotlines of the book.

Also, minor spoilers for the “Misfits and Magic” series on Dropout TV. I reference a clip from the first episode of the show.

I wonder how real a character is.

The simple answer is that it’s not. In a story of fiction, the characters are, by definition, fictional. They are creations of the mind that do not exist in reality but only in the realm of fantasy.

But, even now, by trying to say that characters do not exist in real life, I find myself writing that they do exist—as I just wrote that they exist in fantasy. And, sure, there’s a difference between existing in reality and fantasy… but what is it exactly?

Somewhere characters exist. In the pages of a book, on the screen of our devices, in our earphones.

In our head.

How do we talk about the characters of a story when we want to comment on the latest episode or book we consumed? When I do, I call them by their name, hyping what they did, wondering how they felt and what they thought. I talk about them as if they were real people.

These thoughts have been bugging me since I finished reading Turtles All The Way Down by John Green. It brings me to think about how amazing storytelling is, and how a good writer can create characters that exist.

Who made me ask myself these questions is none other than the protagonist of the book, Aza Holmes, a teenager whose biggest fear is that she’s fictional.

At the time I first realized I might be fictional, my weekdays were spent at a publicly funded institution on the north side of Indianapolis called White River High School, where I was required to eat lunch at a particular time—between 12:37 p.m. and 1:14 p.m.—by forces so much larger than myself that I couldn’t even begin to identify them. If those forces had given me a different lunch period, or if the tablemates who helped author my fate had chosen a different topic of conversation that September day, I would’ve met a different end—or at least a different middle. But I was beginning to learn that your life is a story told about you, not one that you tell.

Of course, you pretend to be the author. You have to. You think, I now choose to go to lunch, when that monotone beep rings from on high at 12:37. But really, the bell decides. You think you’re the painter, but you’re the canvas.

Page 1-21

The tone of that last paragraph (“Of course, you pretend to be the author. You have to. [...] You think you’re the painter, but you’re the canvas.”), that sense of lack of control over your emotions, thoughts, choices, actions, and consequently over your life, is a recurrent theme in the whole book.

A good part of the story is dedicated to Aza’s intrusive thoughts, which do not strictly fixate upon Aza being fictional, but rather on the crippling conviction of having contracted an infection of the bacteria Clostridium difficile.

It’s hard to convey Aza’s thought spirals without being tempted to copy-paste the whole book. It’s one of the things that I appreciated and as well terrified me the most: how understandable Aza’s mental prison was—at least for me. Her voice, thoughts, and feelings permeate everything, and I could follow them.

The very first moment that I felt them was at the end of chapter 5. It starts with Aza explaining in her own words the concept of “intrusive thoughts”.

I have these thoughts that Dr. Karen Singh calls “intrusives”, but the first time she said it, I heard “invasives”, which I like better, because, like invasive weeds, these thoughts seem to arrive at my biosphere from some faraway land, and then they spread out of control.

Supposedly everyone has them—you look out from over a bridge or whatever and it occurs to you out of nowhere that you could just jump. And then if you’re most people, you think, Well, that was a weird thought, and move on with your life.

Page 45

The explanation is uncomfortable but also reassuringly relatable. Yes, I may have had exactly that kind of thought. Yes, I’m terrified to say it out loud, because that would make me a freak. Yes, it’s a relief to hear that maybe it’s not that weird.

Then, Aza continues to explain what real invasive thoughts are.

But for some people, the invasive can kind of take over, crowding out all the other thoughts until it’s the only one you’re able to have, the thought you’re perpetually either thinking or distracting yourself from.

Page 45

For us to get a real taste of what that is like, we are pulled into Aza’s mind. For context, Aza has a Band-Aid on the tip of her middle finger to cover up a little wound (more on that soon). Also, she has been in a filthy river that day while adventuring with her best friend.

You’re watching TV with your mom […] and then a thought occurs to you: You should unwrap that Band-Aid and check to see if there is an infection.

You don’t actually want to do this; it’s just an invasive. Everyone has them. But you can’t shut yours up. Since you’ve had a reasonable amount of cognitive behavioral therapy, you tell yourself, I am not my thoughts, even though deep down you’re not sure what exactly that makes you. Then you tell yourself to click a little x in the top corner of the thought to make it go away. And maybe it does for a moment; you’re back in your house, on the couch, next to your mom, and then your brain says, Well, but wait. What if your finger is infected? Why not just check? […] And then you were in the river.

Now you’re nervous, because you’ve previously attended this exact rodeo on thousands of occasions, and also because you want to choose the thoughts that are called yours. The river was filthy, after all. Had you gotten some river water on your hand? It wouldn’t take much. Time to unwrap the Band-Aid. You tell yourself that you were careful not to touch the water, but your self replies, But what if you touched something that touched the water, and then you tell yourself that this wound is almost certainly not infected, but the distance you’ve created with the almost gets filled by the thought, You need to check for infection; just check it so we can calm down, and then fine, okay, you excuse yourself to the bathroom and slip off the Band-Aid to discover that there isn’t blood, but there might be a bit of moisture on the bandage pad. You hold the Band-Aid up to the yellow light in the bathroom, and yes, that definitely looks like moisture.

Page 45-46

In the bathroom, Aza follows a very well-known and established routine, which includes squeezing hand sanitizer on her fingertip, washing her hands thoroughly for twenty seconds as recommended by the Centers for Disease Control, and, after having carefully dried her hands, digging her thumbnail on the finger pad of her middle finger that she fears is infected and squeeze blood out of it. She has done it so many times that there’s a callus over her fingerprint.

The last step of the routine is to put a new Band-Aid over the wound to prevent infection.

And then… it’s done. The thoughts quiet down and she can go back to enjoy her evening with her mom.

Right?

You return to the couch to watch TV, and for a few or many minutes, you feel the shivering jolt of the tension easing, the relief of giving in to the lesser angels of your nature.

And then two or five or six hundred minutes pass before you start to wonder, Wait, did I get all the pus out? Was there pus even or was that only sweat? If it was pus, you might need to drain the wound again.

The spiral tightens, like that, forever.

Page 47

Aza has OCD (Obsessive Compulsive Disorder). Or at least, it sounds like she does: interestingly, her diagnosis is never spelled out.

I find the choice of not mentioning her diagnosis extremely fascinating: it showed me how little I knew about this condition. I was convinced that OCD was “only” connected with an obsession over cleanliness and tidiness—which can be the case, but how I thought about it was too superficial.

As far as I understand now, the compulsive behaviors—which can be for example opening a callous wound until it bleeds, freeing it from pus, disinfecting it, and applying a Band-Aid on it—are there to calm down the intrusive thoughts. The compulsive behaviors are not the source of the problem: the intrusive thoughts are. The compulsive behaviors are the solution.

They are the only way out for a person who is stuck inside their own head—or so they feel.

There is something about the way John Green writes inner dialogue that gets me. I don’t have OCD. I may have thought in the past that I have intrusive thoughts, but after reading this book I realized, I’m doing fiiiine. Still, I guess there is something in this book because, even though I don’t have this condition, these inner monologues strike a cord within me.

I feel for Ava. Deeply. I’m terrified by her condition and how helpless it feels. And, even though I don’t believe that it’s helpless, I can understand that it feels helpless. I see how maddening it is to be running in circles in your head, and knowing that you’re running, but knowing it doesn’t make it stop—it just makes it more maddening2.

That’s what boggles my mind: connection. I feel connected to Ava and her experience. I follow, at least partially, her thoughts and feelings.

That does not change the fact that she doesn’t exist.

I am aware that it’s not that uncommon of an experience. We all create connections with characters of books, movies, or series we consume: I think often that’s exactly why we consume media at all, especially stories. I don’t know what is it that makes stories and characters so necessary to our lives—and how some of us are hungrier for those than others. Is it the cathartic effect of experiencing secondhand emotions? Is it recognizing us and/or people we know in fictional roles? Is it the fascination of escapism, imagination, and fantasy?

I don’t want to quite go there. Not today. Instead, right now I want to get deeper into the question, of whether characters are real or not. And, specifically, what happens when the character fears to be fictional.

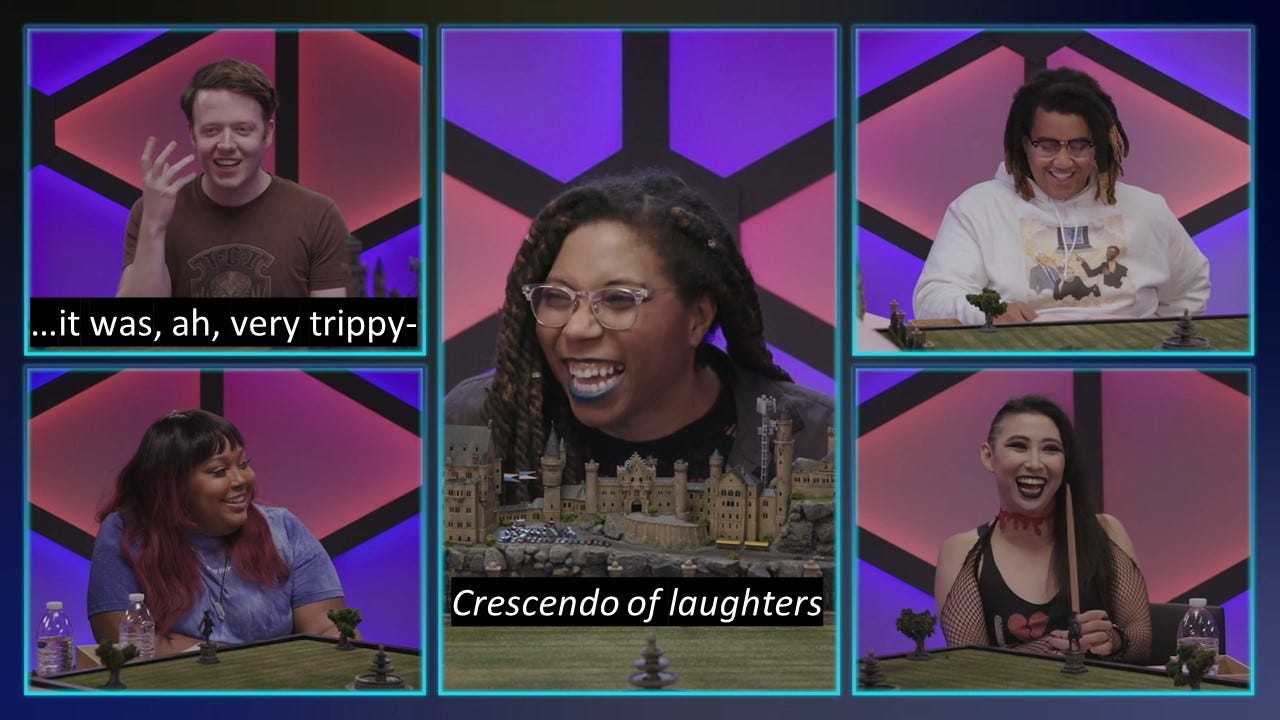

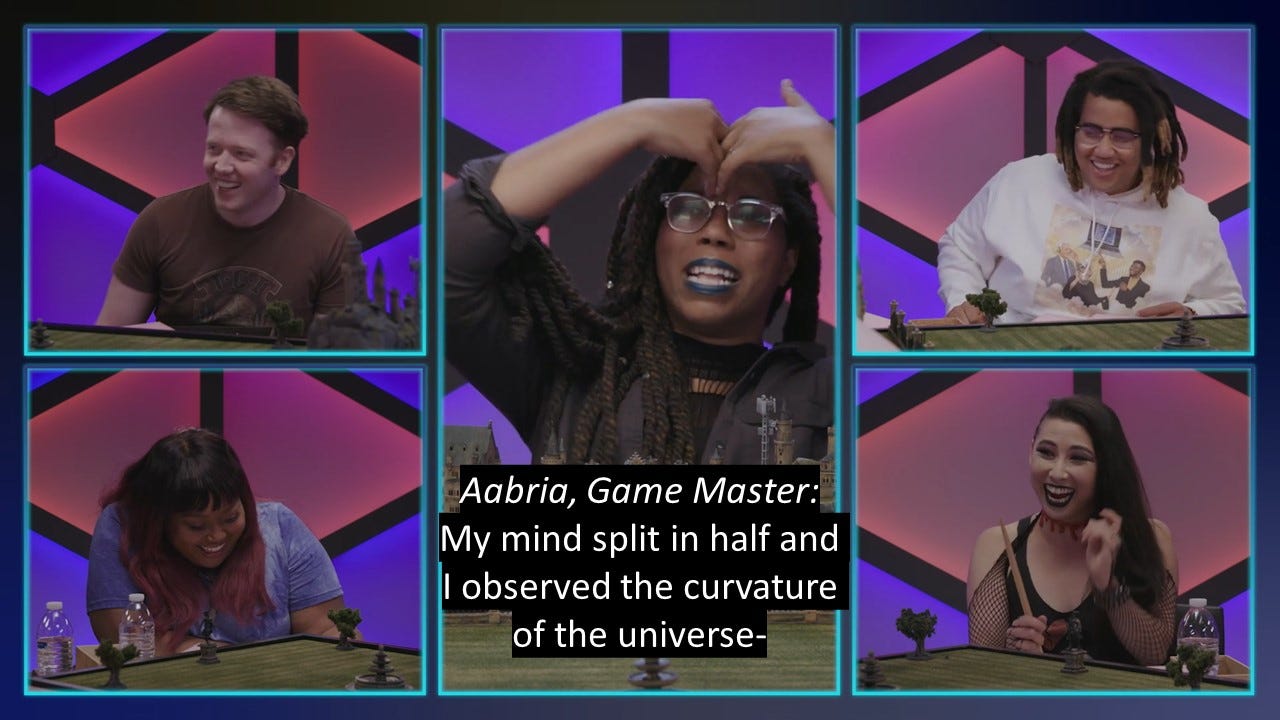

Misfits and Magic is a Harry Potter-inspired mini-series (mini-campaign would technically be the correct term) of a group of comedians and actors playing a collaborative role-playing game. Take Dungeon & Dragons, if you’re familiar with it (technically they are playing with a different game system known as Kids on Brooms) and if you’re not familiar with D&D, then…

Imagine a group of 4 to 6 people at a table. One of them, the so-called “Game Master”, has created a story—or better, the outline of it. The remaining people, the players, listen and interact with the Game Master, and by doing so they create a story. There is an aspect of randomness to it: I’m simplifying it, but you could say that most of the conflicts and encounters are resolved through the roll of dice.

And then there is the role-playing aspect. The players are not playing as themselves: they choose, create, or sometimes are assigned a character, and try to align their actions with what these fictive characters would do.

In a normal game done at home with a bunch of friends, it’s very much up to every single player to decide how hardcore to go with the role-playing aspect. But in Dimension20, the show that created Misfits and Magic, the comedians and actors go full out.

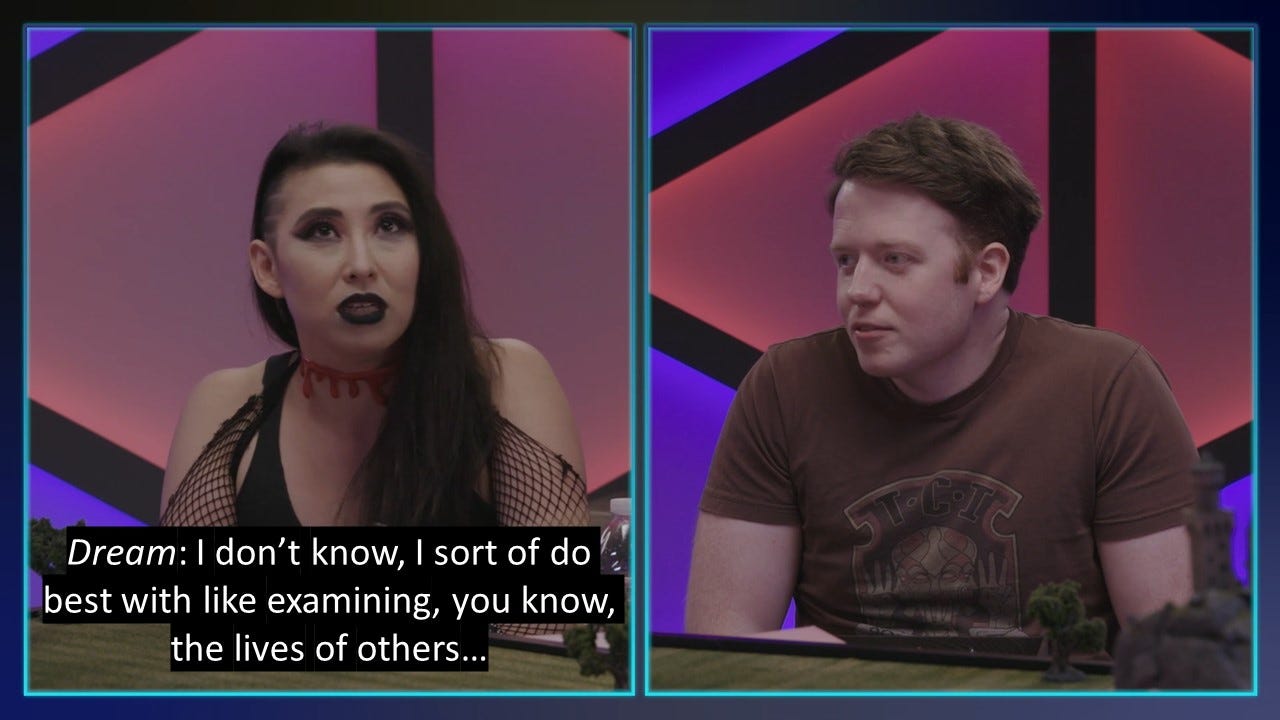

There is a particular scene of that show that is stuck in my head.

Brennan Lee Mulligan is playing as Evan Kelmp. He is the “chosen” dark young wizard with uncontrollable dark powers. The twist is that Brennan decides to play Evan not as a broody, confident, self-absorbed little prick, but as a teenager absolutely horrified by his abilities.

Evan is enrolled in a magic school and makes new friends, one of which is xX_BrokenDream_Xx, a.k.a. Dream (played by Erika Ishii), a teenage girl who is trying real hard to fit into the broody, dark, cool stereotype, and who has a crush on Evan.

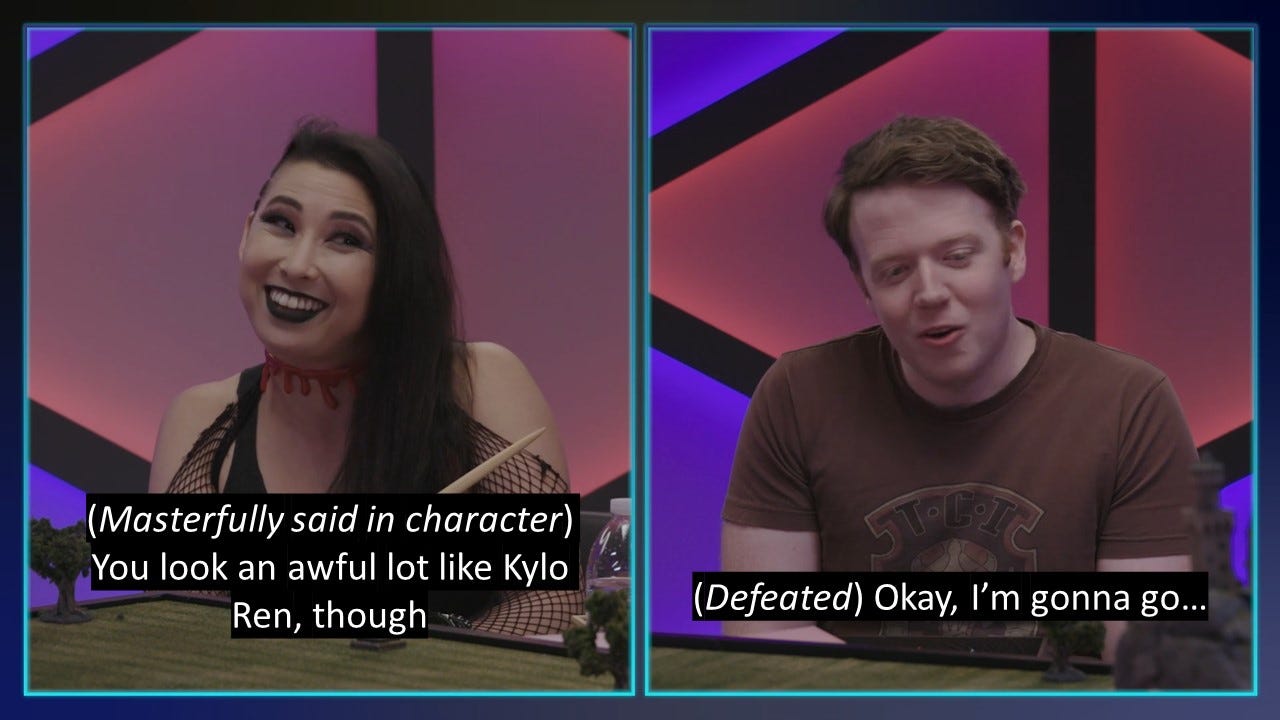

They have this conversation:

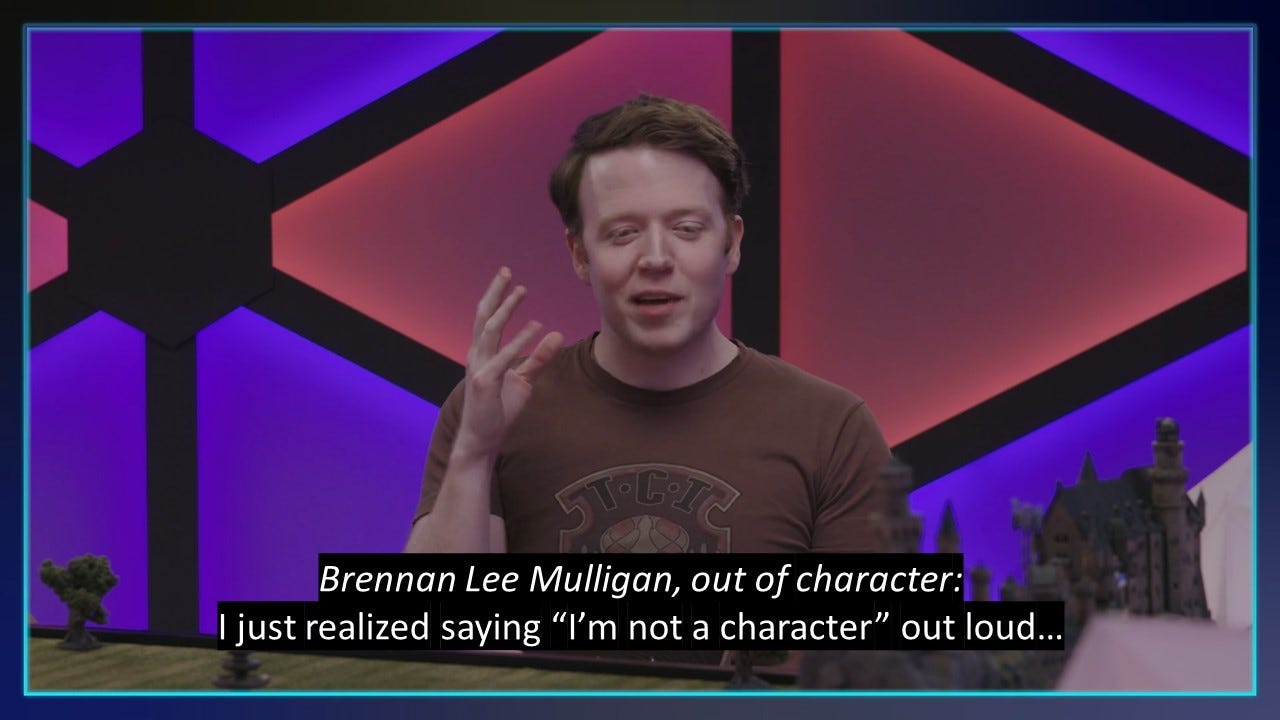

“Evan really believes that”, said Brennan Lee Mulligan. Because, yes, characters believe themselves to be real. And if you’re playing a character, then you need to be faithful to that, even though you know it’s not true.

“Trippy” is the most fitting word for this. Actors are probably the people who know this the best—we “normal” nerds can experience something very similar by playing D&D and such role-playing games. We know how our characters can take a life of their own: at some point, they exist not simply as creations of our mind and are not bound to what we want them to do, but live as more or less independent beings in the liminal space between fantasy and reality.

I’ll go back to Turtles All The Way Down now (but check out Dropout TV if it sounds interesting to you—it’s pretty cool).

The reason why I am trying to wrap my head around these thoughts is because Aza fears something that makes her whole story trippy: she fears being fictional.

And reading that threw me into a weird kind of spiral.

She fears being the “canvas” and not the “painter”. That her emotions, thoughts, and actions are determined by something or someone else. She doesn’t specifically believe that she is a character in a book (even though that idea also comes up at some point), but there are references to an “author” here and there. Let’s go back to that very first page:

If those forces had given me a different lunch period, or if the tablemates who helped author my fate had chosen a different topic of conversation that September day, I would’ve met a different end—or at least a different middle. But I was beginning to learn that your life is a story told about you, not one that you tell.

Of course, you pretend to be the author. You have to. You think, I now choose to go to lunch, when that monotone beep rings from on high at 12:37. But really, the bell decides. You think you’re the painter, but you’re the canvas.

Page 1 (bold mine)

And there’s more of it, still in the first chapter:

[…] and meanwhile I was thinking that if half the cells inside of you are not you, doesn’t that challenge the whole notion of me as a singular pronoun, let alone as the author of my fate?

Page 5

“Okay.” I wanted to say more, but the thoughts kept coming, unbidden and unwanted. If I’d been the author, I would’ve stopped thinking about my microbiome. I would’ve told Daisy how much I liked her idea for Mychal’s art project […]

Page 8

Aza fears being controlled by something or someone else and her mind decides to fixate especially on bacteria.

There is a scene further along the way that in my opinion explains the core of it.

I started telling Davis about this weird parasite, Diplostomum pseidospathaceum. It matures in the eyes of fish, but can only reproduce inside the stomach of a bird. Fish infected with immature parasites swim in deep water to make it harder for the birds to spot, but then, once the parasite is ready to mate, the infected fish suddenly start swimming close to the surface. They start trying to get themselves eaten by a bird, basically, and eventually they succeed, and the parasite that was authoring the story all along ends up exactly where it needs to be: in the belly of a bird. The parasite breeds there, and then baby parasites breeds there, and then baby parasites get crapped out into the water by birds, whereupon they meet with a fish, and the cycle begins anew.

I was trying to explain to him why this freaked me out so much but not really succeeding […] but I couldn’t stop myself, because I wanted him to understand that I felt like the fish, like my whole story was written by someone else.

I even told him something I’d never actually said to Daisy or Dr. Singh or anybody—that the pressing of my thumbnail against my fingertip had started off as a way to convincing myself that I was real. As a kid, my mom had told me that if you pinch yourself and don’t wake up, you can be sure that you’re not dreaming; and so every time I thought maybe I wasn’t real, I would dig my nail into my fingertip, and I would feel the pain, and for a second I’d think, Of course I’m real. But the fish can feel pain, is the thing. You can’t know whether you’re doing the bidding of some parasite, not really.

Page 105-106

And finally, another little part. This one made me wonder something.

Felt myself slipping, but that’s a metaphor. Descending, but that is, too. Can’t describe the feeling itself except to say that I’m not me. Forged in the smithy of someone else’s soul. Please just let me out. Whoever is authoring me, let me up out of this. Anything to be out of this.

But I couldn’t get out.

Three flakes, the four arrive.

Then many more.

Page 211

And what I wonder is, how the hell was it for John Green to write this?

It is jokingly said among writers that our job is to make our characters suffer because they just can’t get right away what they want: that doesn’t make for a good, entertaining story.

But this… this feels like a whole different level of suffering.

I think this is because we as readers know, Ava’s fear is real. The thing that terrifies Ava, that infests her mind, that ominous doubt that has her stuck in pain, is real. She can’t be sure of it, and that not-knowing is crippling. But we know it.

I know it. And I just don’t want her to know.

This is my reaction, and it may be different from other people. But the most interesting thing that I noticed while reading and that throws me in a loop is that I don’t want Ava to focus on the question of whether she’s fictional or not. I don’t want her to spend time and energy wondering about that. I don’t want her to find out the truth; actually, I don’t even want her to want to figure this out.

Because I know that the answer won’t bring her peace, and all I want for her is to live a peaceful, happy life.

Ava. A fictional character. Who has not a life, outside of a freaking book. Yes, I want her to have a peaceful and happy life.

She’s not real. But at the same time, she is? Not in the “real world”. But maybe in some little recess of my mind?

At this point, my brain freezes and decides to stop doing the math, probably because it would throw me into some existential crisis of sorts. But exactly this weird thinking spot fascinates me.

I just find it interesting to realize that as an external observer, I find Ava’s question to be not as pivotal as she thinks it is. Figuring out if she’s fictional or not does not improve her quality of life, whether it is true or not. And I mean, she knows it—it’s not that she wants to think about it, it’s more that she can’t stop thinking about it.

There is just something interesting in realizing that maybe whether our biggest fear is real or not is—sometimes—not that important. It’s the act of fearing something that makes us suffer.

Does it mean that we should just stop feeling fear, and then we’re happy? Just STOP, and there, you’re good to go. Yeah… it doesn’t work that way.

Also, does it mean that we should stop asking ourselves complicated questions? As in, are we the painter or the canvas of our lives?

I believe that there must still be a place for that. As for how, when, and in which measure, to tackle that would take much more than this blog post.

I guess, the whole reason why I wanted to write this, it’s because all of this fills me with wonder. The fact that little inked signs on white paper end up making me think so much and throw me in such loops makes me feel alive.

This is truly, for me, for how cheesy it sounds, the magic of writing. There is something otherworldly in the way an author can make a character feel real in my head, and affect me. It doesn’t simply make me think, it makes me feel, and it doesn’t simply make me feel, it makes me think.

John Green created a character who fears being fictional and suffers because of it. And even though it’s true—Ava is fictional—at the same time I believe that John Green, as any good author can do, created something that has also a bit of a life of its own. What happens in Turtles All The Way Down may have been under his complete control—and even that I think it’s debatable—but for sure what happens after is completely out of his control.

How Ava lives in the minds of the readers and how she affects them, that’s something he can’t author.

I can’t quite explain exactly how he did it, not yet. But he did, and that is, as an aspiring writer, what I aim to do: create characters that have a life of their own.

That is one of the mesmerizing things of stories, and I love it.

If you have any thoughts on what I shared, let me know by simply replying to this email or leaving a comment!

Take care,

Rye Youbs

All the page references are from the Hardcover edition printed by Dutton Books (Penguin Random House LLC), 2017.

It may be that I’m making this book sound much more “desperate” than it is. There is so much more than this, I promise—I am ignoring huge parts, if not the main parts of the plot, which entail, among other things: the disappearance of a billionaire and a hundred-thousand-dollar reward for any information on his whereabouts; encounters with Davis Pickett, son of said billionaire; and Ava’s best friend Daisy and her Star Wars fan fiction.

Ooh I need to read this book! I love the concept of questioning where characters really exist and how they can feel more real than things in our own lives when they are equally as intangible. I think characters mainly live in reader’s thoughts and sometimes their dreams (aspirations). A great character (whether morally good or bad) stays in our mind because I believe there is something about them we find relatable. Even when our favorite characters are opposite of us in every way, I think our attraction to them can speak to our hidden desires or insecurities within ourselves. I think the best characters can inspire us to take actions our own life or they can give us a reprieve from our daily troubles that in turn gives us the strength to face our own difficult realities.